Building Sorty: local-first AI document sorting

Tuesday, January 27, 2026

I’ve been paperless for a long time. Part organization, part paranoia. I sleep better knowing the important stuff is scanned, searchable, and stored somewhere sane.

My weekly ritual is simple:

- scan anything new (receipts, school letters, government mail, medical stuff)

- rename it to something human

- file it into the right folder

- shred what doesn’t need to exist on paper anymore

Then we moved.

After an international relocation, my “inbox” wasn’t a few documents. It was 200+ scans with names like “Scan Jul 17, 2025 at 12.17 PM” and “1 Screenshot 2.” The job was obvious. The motivation was not.

- A typical filename looked like “Scan Jul 17, 2025 at 12.17 PM.pdf.”

- A typical decision looked like “Is this immigration, tax, school, or health?”

- Multiply that by 200 and you get the kind of task that sits there, untouched, for months.

Around the same time, I kept seeing demos of Claude Cowork: a local agent browsing folders, renaming files, sorting everything automatically. The capability was clearly there.

But I had one non-negotiable constraint: For this category of documents, I wanted a local-first design with explicit human-first reviews built into the flow.

So I built my own.

I called it Sorty.

The constraint: do it with AI, but keep it on my machine

The product idea was straightforward: Extract meaning from documents locally, propose a filename and destination folder, let me approve changes, then execute in a predictable, reviewable way.

No cloud OCR. No sending document text to an external LLM. Local-first by design.

I started where I start most things now: fast, ugly, and useful.

A Python CLI prototype I could run against a folder, iterate on, and delete without mourning. Claude Code and Cursor made that part almost unfairly easy. Within hours I had something that felt real:

- document ingestion

- OCR plus extracted text

- a first-pass rename and move workflow

- enough scaffolding to move quickly

And then I hit the part of AI-assisted building that still surprises people.

The output looked right. The system was wrong.

I’ve seen the same failure mode inside product orgs. When output gets cheap, it becomes easy to confuse “plausible” with “correct.” The only real defense is ownership: insist on foundational context, build a verification loop, and make the system’s behavior legible to the human who has to live with the consequences.

The failure mode: confidently building the wrong solution

Sorty was improving with each iteration, but it wasn’t improving in the way I intended.

When I dug in, I realized what was happening.

Claude was hard-coding a sorting schema based on my examples. I found a growing mapping table that was basically my prompt examples turned into code.

Instead of building a pipeline that interpreted each document using the primitives I was asking for (local OCR, on-device intelligence, user review), it was quietly turning my examples into a ruleset. That can look fine early on. It also becomes fragile the moment your folder stops resembling your prompt.

So I asked it directly, in plain language: “Are you actually using Apple’s on-device intelligence and vision frameworks here?”

Its response was essentially: those capabilities aren’t available.

That mismatch is the dangerous part. Not malicious. Just stale.

Apple’s on-device capabilities were real, and I knew it. Post WWDC 2025, the latest OS releases made local-first intelligence a practical foundation for this kind of workflow. Sorty existed because I trusted that direction enough to build around it.

My coding assistant didn’t share that mental model. So it optimized for what it could “prove” from my prompt instead of what I intended from the platform.

The fix: foundational context, then rebuild around trust

Once I treated this like any other ambiguity, the path was obvious:

- bring context (official docs, current APIs, real references)

- re-anchor the design around what actually exists today

- rebuild the pipeline so it cannot quietly fall back into a hard-coded guesser

I also installed a community-made plugin that pulls in current Apple developer documentation, because this is the reality of building with coding assistants: if their knowledge is stale, they will fill the gaps with confident fiction.

Once the model had the right foundational context, everything improved, including the decisions:

- what can be done fully offline

- what should never happen without explicit review

- where the UX needs guardrails because rename and move is irreversible once you’ve made a mess

At some point the CLI stopped being a script and started being a product. So I used the CLI as a spec and began shaping a SwiftUI app.

Three rules I would not compromise on

This workflow touches high-stakes documents. That changes the standard. “Works” is not enough. The UI has to show what is happening and why, in a way that survives real use.

Three rules became non-negotiable:

- Local by default. Sensitive content stays on-device.

- Human review for destructive actions. No silent moves. No surprise renames.

- Evidence in the interface. If it proposes a rename or move, it shows what it used and what will change before anything changes.

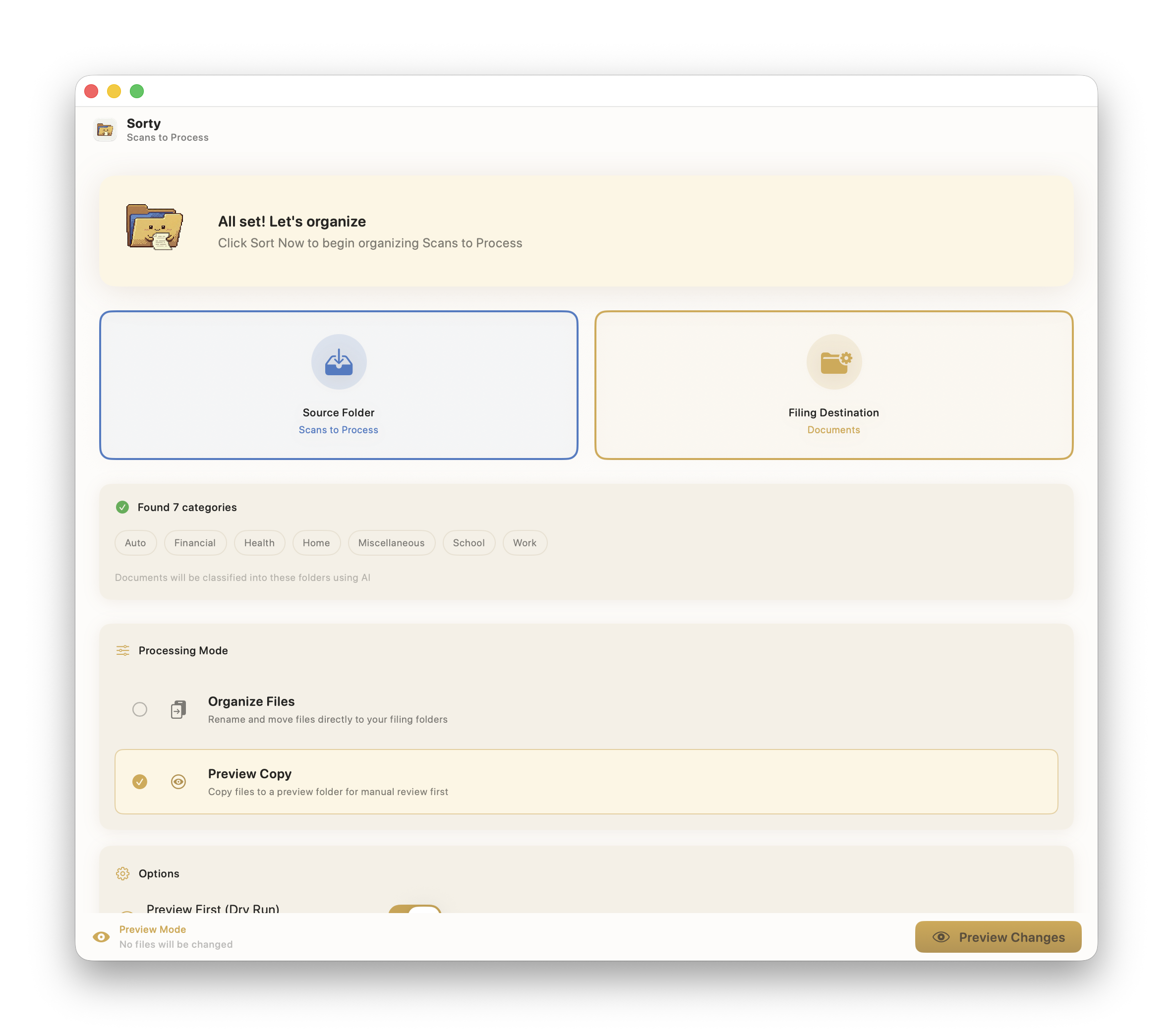

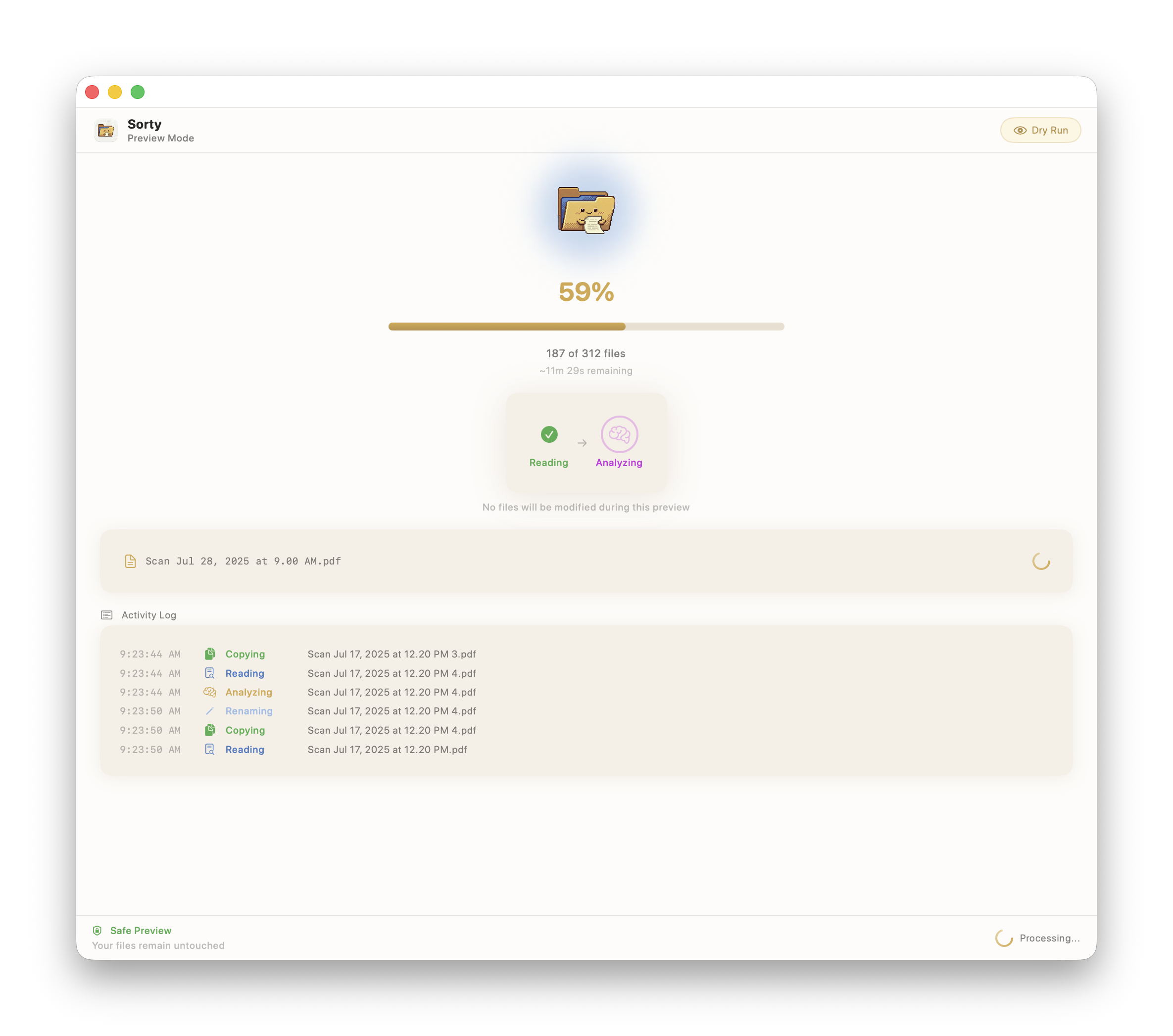

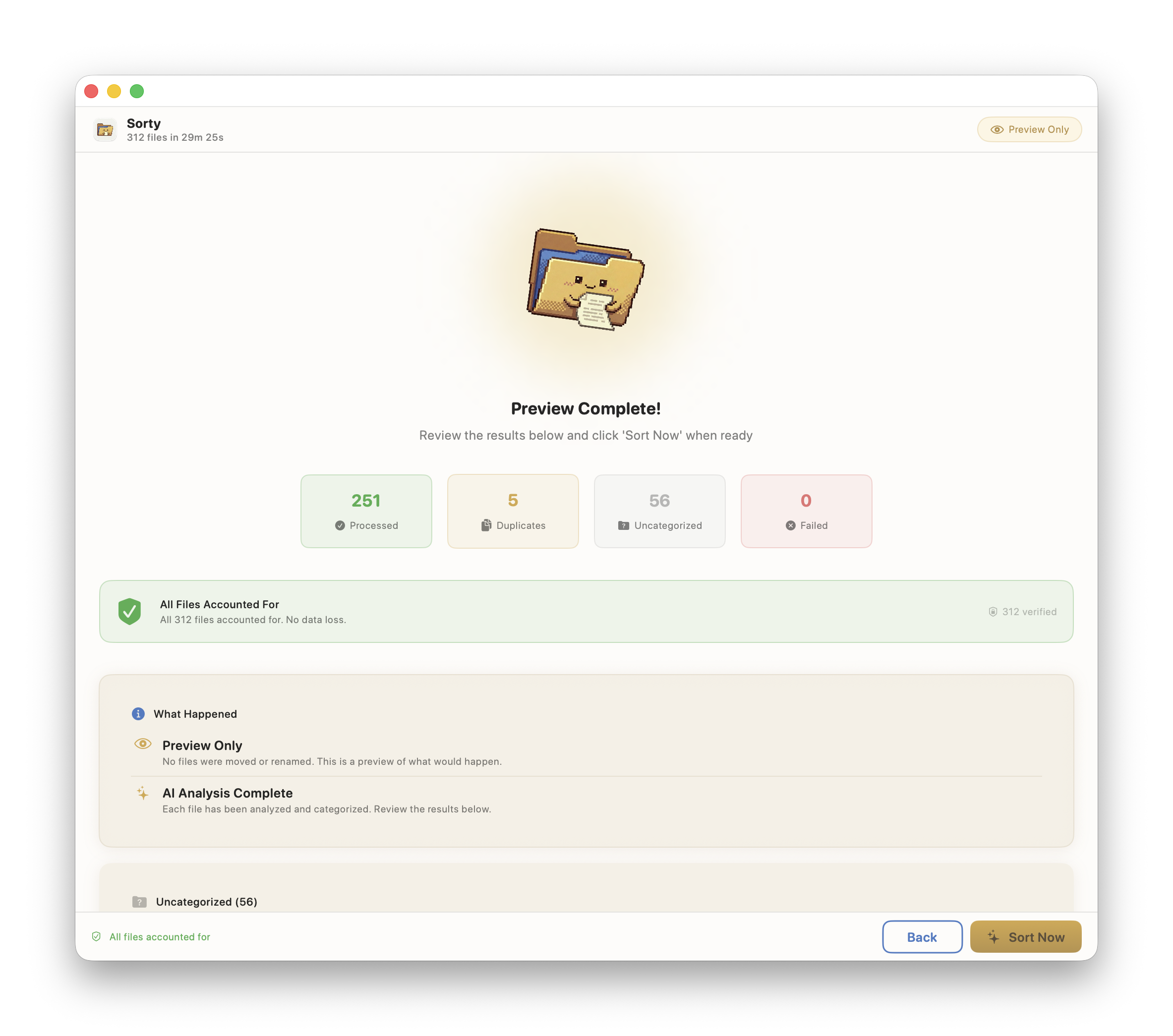

That last point shaped Sorty more than I expected. I added a Preview mode because I don’t want to infer what the system did after the fact. I want to see the exact set of proposed changes, make edits, and approve it before anything touches the filesystem.

What Sorty does

Sorty takes a folder of messy scans and helps you turn it into an organized archive:

- extracts text locally (OCR stays on-device)

- proposes:

- a meaningful filename

- a destination folder

- shows a review UI (approve, edit, skip)

- includes a Preview mode so you can validate changes before they execute

- executes renames and moves in a way you can reason about later

One more constraint I wrote down early and kept: Sorty will not auto-delete, auto-archive, or silently move anything. If a file changes location, you see it and approve it.

The real lesson: AI collapses build time, not ownership

Lately, the loudest change has been speed. You can get from idea to shippable prototype in hours.

But building Sorty reinforced something I’ve started to treat as a rule: AI collapses the cost of output. It does not replace ownership.

If anything, it raises the bar on the human parts:

- defining constraints that actually matter (privacy, trust, auditability)

- noticing when the system is wrong even if the UI looks right

- validating assumptions with foundational context

- designing the workflow so errors are hard to make and easy to catch

The difference, for me, is whether I’m driving or delegating.

- Delegating looks like accepting plausible output because it compiles.

- Driving looks like setting constraints, forcing proof, and designing the workflow so mistakes are hard to make and easy to catch.

Sorty only became real once I stopped treating the model like an oracle and started treating it like a capable teammate who still needs context, verification, and accountability.

What I’m taking forward

Speed changes what is easy to produce. It does not change what is safe to ship.

The most valuable work moved upstream: constraints, foundational context, verification, and making the system’s behavior obvious to the person accountable for it.

The model can accelerate the build. Ownership still decides whether the system is real.